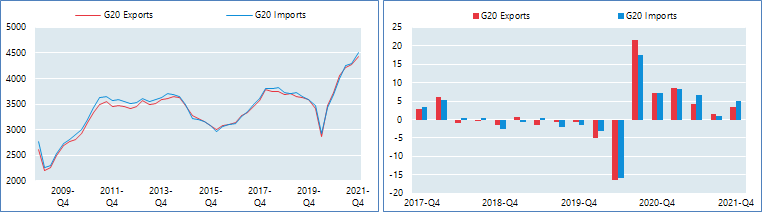

Acceleration in merchandise trade bolsters recovery in G20 trade, but growth in services trade eases

24 Feb 2022 – Following a slow third quarter, G20 international merchandise trade accelerated in value terms in Q4 2021, partly due to high commodity prices, in particular for energy. While shipping costs kept the value of trade in transport services at record highs, trade in other services showed a slowdown notably in Europe, possibly reflecting a tightening of Covid-19 related restrictions towards the end of the year.

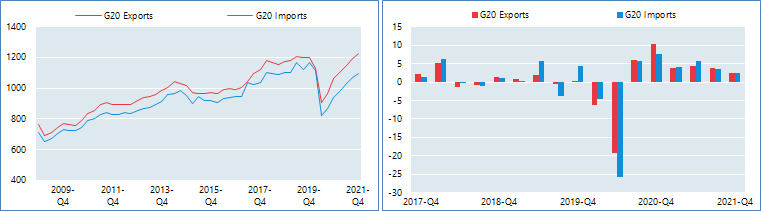

Growth in G20 international merchandise picked up in Q4 2021, with exports up 3.4% and imports up 5.0%, with respect to the previous quarter and measured in seasonally-adjusted current US dollars. This compares to the slower growth (1.5% for exports and 0.9% for imports) recorded in Q3 2021. Energy price increases continued to fuel merchandise trade growth in value terms, while pressure on supply chains, including for semiconductors, appears to have eased towards the end of the year.

Growth in exports and imports of services for the G20 is estimated at around 2.5% and 2.4% in Q4 2021, respectively, compared with the previous quarter and measured in seasonally-adjusted US dollars. The preliminary estimates compare to the rates of 3.8% and 3.5% recorded in Q3 2021 for exports and imports. Services trade continued to expand at a sustained pace in North America and most of East Asia, while growth slowed down in Europe.

In 2021, annual merchandise exports and imports for the G20 expanded by 25.9% and 26.1%, respectively, with values around 16% above their 2019 levels. While high commodity prices explain part of the increase, stimulus packages also played a role by spurring the demand for traded goods. Annual growth in exports and imports of services is estimated at around 15.0% and 11.3%, respectively. While transport costs skyrocketed, travel, which includes the expenditure of non-residents abroad, recovered but remained subdued. Trade in computer, business and financial services performed well across most of the G20 economies in 2021.

G20 merchandise trade

Based on figures in current prices (billion US dollars), seasonally adjusted

A recovery in trade in vehicles and parts helped push merchandise trade growth in North America in Q4 2021, with exports from the United States (up 7.1%), Canada (up 6.7%) and Mexico (up 6.0%) all recording strong growth. Import growth for Canada (up 7.2%) and the United States (up 5.9%) was largely driven by higher purchases of home electronics and mobile phones.

Merchandise exports instead contracted in Argentina and Brazil (minus 7.3% and minus 5.0%, respectively), with lower shipments of metal ores and soybeans (mostly to China) weighing in particular on the Brazilian figures. Imports, on the other hand, expanded by 13.0% in Argentina and by 11.5% in Brazil, the latter driven by energy products, electrical machinery and fertilisers.

Merchandise trade picked up in Europe in Q4 2021, following the weak growth seen in Q3 2021. Exports and imports in the European Union (EU-27) expanded by 2.3% and 5.1%, respectively. All the major European G20 economies showed robust merchandise trade growth: France (exports and imports up 2.6% and 6.3%, respectively), Germany (up 2.2% and 5.8%) and Italy (up 2.5% and 4.5%), with higher purchases of energy products driving the import figures and trade in vehicles and parts recovering. Merchandise exports and imports of the United Kingdom expanded by 3.2% and 5.3%, respectively, with chemicals, machinery and transport equipment driving exports and energy products contributing to imports growth.

Electronics and vehicles (including e-cars) continued to spur exports growth for Korea (up 5.2%), while Japan saw more moderate growth in both exports (up 0.5%) and imports (up 2.2%). Chinese merchandise exports (up 4.6%) and imports (up 0.9%) rebounded in Q4 2021, after the much weaker figures in the previous quarter. Electronics and integrated circuits helped boost growth in exports, with integrated circuits also fuelling import growth along with soybeans and metal ores. India, with exports up 2.2% and imports up 10.7%, and Indonesia (up 8.9% and 13.1%), also posted solid merchandise trade figures in Q4 2021. Falling prices for metals and lower shipments of coal and fuels affected export growth for Australia (minus 3.5%), while imports expanded by 7.5%, largely driven by higher spending on vehicles, telecommunication equipment and home electronics. Exports from South Africa also contracted by 2.1% in Q4 2021, reflecting drops in its major exports of metal ores, fruits and electrical machinery, while imports increased by 3.3%.

In 2021 as a whole, merchandise trade values for the vast majority of the G20 members more than recovered the drops recorded in 2020. Exports and imports expanded by 23.1% and 21.3%, respectively, in the United States, with energy products and pharmaceuticals recording significant growth on the exports side. Similarly, annual exports and imports rose by 20.8% and 25.1% in the European Union. Electronics (integrated circuits, mobile phones, displays and computers) continued to propel merchandise exports from Korea (up 25.6%) and China (up 32.2%). Machinery and vehicles and parts contributed to total merchandise exports growth for Japan (up 18.3%), while imports increased by 21.3% over the year. Leading exporters of primary commodities benefitted from high demand and steep price increases, with merchandise exports soaring in 2021 for Russia (up 47.5%), India (up 42.1%), Indonesia (up 38.4%) and South Africa (up 44.9%).

G20 trade in services

Based on figures in current prices (billion US dollars), seasonally adjusted

Note: the Q4 2021 trade in services values are preliminary estimates based on available data, covering about 60% of exports and imports for the G20 aggregate.

Services trade showed a mixed picture in Q4 2021. Following the expansion recorded in the previous two quarters, services trade in Europe slowed down in Q4 2021. Services exports increased by 1.8% in France, with weak sales of financial and insurance services partially offsetting growth in travel (up 15.9%) and transport (up 4.3%). German exports contracted by 2.3%, while imports increased moderately by 1.2%. The United Kingdom recorded a slowdown in both services exports (minus 2.4%) and imports (minus 2.5%), while exports and imports of Italy increased by 1.6% and 3.6%, respectively.

Turkey’strade in services continued to expand in Q4 2021. Exports grew by 4.0%, while imports rose by 8.0% reflecting strong purchases of computer and business services. Similarly, Russia’s services trade expanded markedly, with exports increasing by 8.4% and imports surging by 19.4%.

An easing of travel restrictions and high transport costs sustained trade in services growth in North America. The United States saw a 6.6% rise in services exports, with travel and transport up by 39.4% and 11.3% in Q4 2021. Imports grew more moderately by 4.3%. Similarly, Canada’s services exports and imports expanded by 6.5% and 6.1%, respectively, compared to the previous quarter.

Transport, computer and business services continued to boost trade in services growth across East Asia. Exports increased by 5.5% in Korea, with construction, of which Korea is a leading exporter, picking up strongly (up 55.9%) following three quarters of contraction. China also saw marked growth of 6.1% in services exports, fueled by higher sales of transport, computer and business services. Imports expanded by 4.6% in Korea and by 3.8% in China. Japan, on the contrary, experienced a decline in both services exports and imports (minus 3.9% and minus 5.0%, respectively), reflecting lower trade in all services but transport.

Owing to prolonged entry restrictions, which depressed travel receipts, services exports contracted further in Australia, recording a 4.9% fall in Q4 2021. However, services imports increased by 4.9% driven by transport (up 21.8%). In Brazil, services exports grew by 0.7%, while imports rose by 3.4% on higher purchases of business and transport services.

For 2021 as a whole, most G20 economies showed a robust rebound in trade in services compared to the previous year, although in many cases values remain below pre-crisis (2019) levels due to subdued travel figures.Exports of services from Korea and China, up 34.8% and 42.5% in the year, respectively, are an exception: soaring transport receipts, as well as buoyant figures across all services, drove total exports well above their 2019 levels. Japanese exports and imports expanded more moderately over the year (up 4.2% and 5.3%, respectively), while strict travel restrictions continued to weigh heavily on Australia’s services exports (down 8.4% compared to 2020). Services exports and imports increased by 8.6% and 16.2% in the United States, with financial and business services driving export growth, and transport and travel propelling import growth. In Europe, annual exports from France (up 18.0%), Germany (up 15.6%) and the United Kingdom (up 8.1%) were all close to their 2019 levels, largely reflecting dynamic trade in business and financial services. With travel receipts twice as high as in 2020 (but still 30% below their 2019 levels), Turkish exports of services jumped by 56.2% in 2021.

מנופי ZPMC מגיעים לנמל אשדוד. יוצבו ברציף 21 ויחלו בעבודה תפעולית לקראת ספטמבר | צילום: פבל טולצ'ינסקי

מנופי ZPMC מגיעים לנמל אשדוד. יוצבו ברציף 21 ויחלו בעבודה תפעולית לקראת ספטמבר | צילום: פבל טולצ'ינסקי